Do not handle an injured or grounded flying fox. NO TOUCH, NO RISK.

If you find an injured, sick or orphaned flying fox or bat, call Bat Rescue 3062 6730; or Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 0488 228 134.

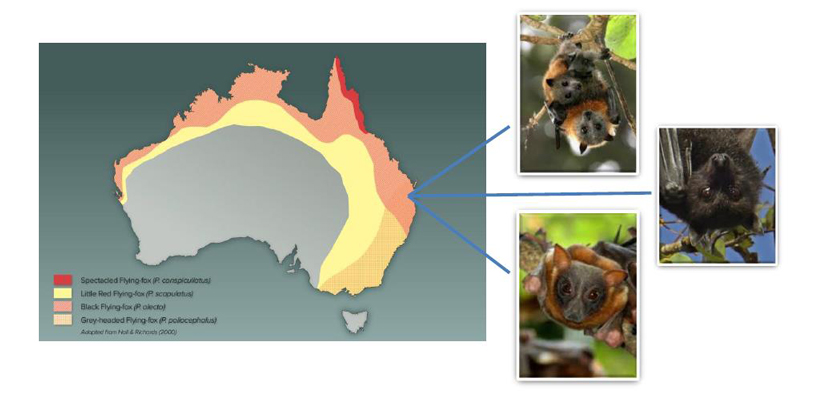

There are three species of flying foxes present in Ipswich.

- Black flying fox (Pteropus alecto): The largest of the flying fox species

- Grey headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus): Listed as Vulnerable (National Conservation Status)

- Little red flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus): A nomadic species that typically visit in summer

All three species and their habitat are protected under the Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992.

All three species and their habitat are protected under the Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992.

Flying foxes are complex, highly social and mobile native animals. They make a significant contribution to environmental health and the economy through their role as essential long-distance pollinators and seed dispersers for native forests.

Flying foxes in Summer

Typically there will be an influx of flying foxes during the warmer months, particularly the nomadic little red flying foxes.

Typically there will be an influx of flying foxes during the warmer months, particularly the nomadic little red flying foxes.

The little red flying fox is often the main species causing concern for human residents. They visit Ipswich to take advantage of a flowering of native trees across South-East Queensland in spring and summer, before continuing their migration northwards.

Their high seasonal numbers often exacerbate the volumes of noise, smell and damage in a colony.

Flying foxes, like humans, are susceptible to heat stress and death if temperatures are above 38 degrees Celsius or when there is a combination of high heat and high humidity.

It is important to minimise the stress on flying foxes, as mass deaths can be a serious public health issue.

Typically, flying foxes will spread into lower vegetation in an effort to stay cool. They may end up in unexpected locations on your property.

DO NOT TOUCH flying foxes. Contact a wildlife carer for assistance if needed.

- NEVER touch a flying fox. No touch, no risk.

- If a flying fox is injured or has come to ground in your backyard DO NOT TOUCH it, keep people and pets away and contact:

- Bat Rescue 3062 6730 (Ipswich)

- Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 0488 228 134

In the unlikely event you are bitten or scratched, wash the injury site thoroughly but gently with soap and water and seek medical advice straight away.

If the animal is dead, wear protective clothing and gloves and use a shovel/tongs to place the bat into a heavy duty plastic bag or lined bin for disposal. Never handle a flying fox directly with your hands.

If there are a large number of dead bats and you require additional collections to dispose of them, please contact Council on (07) 3810 6666.

Importance of flying foxes

Flying foxes play a vital role in the regeneration of native forests. Due to their nocturnal feeding habits and extensive feeding ranges, flying foxes are able to pollinate tree species that produce most of their nectar at night and are thus not serviced by day-feeding birds and bees.

Flying foxes are the most important species in the country for pollination and long-distance dispersal of Eucalypt species. This has important flow-on effects for other native species such as koalas that rely on flying fox pollination for the growth and maintenance of their own feeding and shelter trees.

For more information see the Importance of Flying Foxes from the Queensland Government.

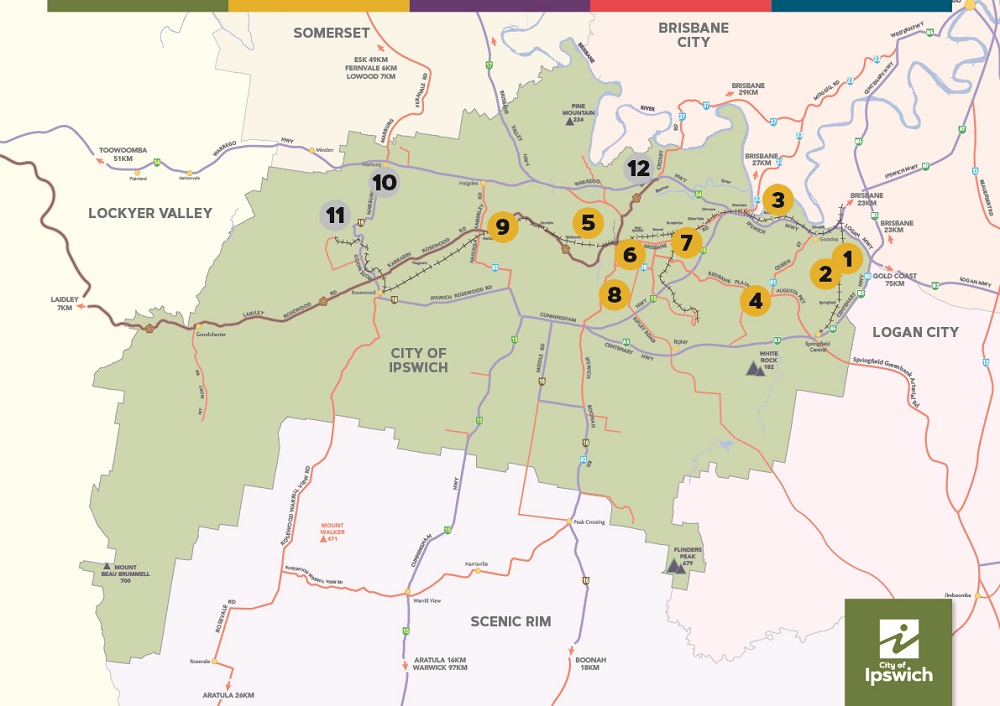

Flying fox colonies in Ipswich

Subject to change in season and food availability, Ipswich is home to between four and ten flying fox camps. All are generally located in roosts found along natural or man-made water courses in urban, peri-urban and rural areas of the city.

Map legend:

- 1 Pilny Reserve

- 2 Stephen Cook Memorial Park

- 3 Pan Pacific Peace Gardens

- 4 Philip Street

- 5 Woodend

- 6 Queens Park

- 7 Lorikeet Street Reserve

- 8 Deebing Creek

- 9 Poplar Street Reserve

- 10 Marburg (not recently active)

- 11 Tallegalla (not recently active)

- 12 Chuwar (not recently active)

Flying foxes typically prefer roosting in trees near creeks with a thick understorey of shrubs and grasses, though a loss of preferred habitat means they might roost in less desirable places such as backyard gardens and local parks.

The Woodend colony was previous one of the largest in South-East Queensland, at times hosting more than 250,000 flying foxes. During the 1980s, the Camira colony had hundreds of thousands of flying foxes. The majority of those two colonies originally came from Sapling Pocket, where one of the largest colonies in Queensland lived until continued disturbance dispersed the colony. Following degradation of roosting habitat at Woodend, a number of smaller local roosts emerged. There is now a scattering of small colonies across Ipswich, none of which reach the population sizes common in the 1980s.

Due to the decreasing availability of natural habitat as a result of urbanisation and destruction of historic habitat, flying foxes are coming into increasing contact with humans.

Flying foxes are not a pest species or vermin and are never in ‘plague proportion’. Living in colonies means that large numbers of the one species are often congregated in a single small area as a totally natural and common way of living.

FAQ: Why has the population of a nearby colony exploded overnight?

The little red flying fox is a nomadic species that move seasonally in response to the patterns of flowering Eucalypts and paperbarks. Little reds are noticeably smaller than the other flying fox species that are present in Ipswich permanently.

Little reds can often be seen roosting in extremely close proximity to one another. As the species exist as a large nomadic population that packs huge numbers of bats in a small area, summer influxes of little reds temporarily swell the size of the colony, increasing the volume of noises and smells for a period of time.

As little reds are seasonal, generally by April they leave Ipswich and continue their migration northwards, leading to a drop in local flying fox numbers.

FAQ: I hear that flying foxes carry disease - is that true?

Like all native and domestic animals, flying foxes can carry diseases. Research by the Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, Queensland Health, Biosecurity Queensland and others has shown that some species of bat act as a natural reservoir of infection for both Hendra virus and Australian bat lyssavirus.

Fortunately, there are suitable and easy solutions to reduce the level of risk.

Most importantly – NEVER TOUCH or handle a flying-fox. No touch, no risk.

If a flying fox is injured or has come to ground in your backyard DO NOT TOUCH it, keep people and pets away and contact:

- Bat Rescue 3062 6730 (Ipswich)

- Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 0488 228 134

Only those few trained individuals who are protected by vaccination and suitable equipment should handle bats. This advice is not limited only to flying foxes but is also true for insectivorous bats.

Keep horse watering and feeding locations away from trees where flying foxes may feed or roost.

For more information on diseases related to flying foxes and measures to minimise the risk to humans and animals, see Queensland Government webpages on viruses hosted by flying foxes

FAQ: Should I be concerned with flying foxes feeding in my trees?

Flying foxes usually choose to feed on nectar from native Eucalypt species, as well as fig trees and select fruit trees. Fruit trees such as mango trees are generally a secondary food source, but used more frequently in urban areas when local flying fox numbers are high. Flying foxes will generally utilise a food source for a very limited time and move on when it is depleted. Most trees will only be used for a couple of weeks every year.

- Fruit that has been partly eaten by flying foxes should not be consumed by people.

- Fruit covered in guano (bat droppings) should be washed thoroughly and peeled prior to consumption.

- Non-peelable, contaminated fruit such as mulberries should be avoided as a matter of good hygiene practice.

- Fauna-friendly netting or placing paper bags over fruit can be an effective technique in deterring feeding flying foxes. For more information on suitable netting techniques: Netting Fruit Trees.

FAQ: Are flying fox numbers increasing?

Overall flying fox numbers have declined in the last century due to widespread clearing of native foraging and roosting habitat for agriculture and urban development, and culling practices across their range.

These habitat losses have accumulated to about two-thirds of South-East Queensland’s native vegetation, with an almost 90 per cent reduction of broad-leaf paperbark forests, which are the primary source of winter food for nectar-feeding flying foxes.

Flying foxes are highly nomadic species that move thousands of kilometres across Australia in search of food. Localised events such as bushfires, droughts, food shortages or food abundances will greatly influence flying fox numbers and may lead to short-term influxes at suitable locations. This does not mean that they will remain in those numbers long-term.

The reduction in habitat has forced flying foxes to find other habitats, including patches of bushland in urban areas. Flying foxes have highly complex social structures and communicate knowledge of feeding and roosting sites across groups and even generations. Therefore, their choice of urban roosting sites may be linked to historic connections with the site prior to development and is also influenced by available water and food within the urban landscape and backyard plantings.

This has led to increased contact and conflict with humans. Where large roosts occur close to residential areas, the potential for conflict increases as the noise and odour associated with their daily interactions may disrupt the lifestyle of nearby residents.

Managing flying foxes

Activities which may impact flying foxes are regulated but there are actions you can take to minimise the impacts on your property and family.

Any unauthorised attempts to disturb flying fox colonies would not only be illegal but also highly unlikely to be effective.

When managing flying fox roosts, considerations around the general welfare of the species must be taken into account, including current mating or breeding seasons, species movement patterns and regional food availability.

FAQ: What can I do to manage flying foxes roosting on my property?

Flying fox roosts are protected under the Queensland Nature Conservation Act 1992, it is an offence to destroy a roost, attempt to drive away flying foxes from a roost and disturb a roost, unless a person is authorised to do so.

However, all persons are authorised to undertake low impact activities on their property (such as mulching, mowing, weeding and watering), but the activities must be done in accordance with the Code of Practice: Low impact activities affecting flying fox roosts, Nature Conservation Act 1992.

Operating outside of the code of practice without an authority may have legal consequences.

Private residents can apply to the Queensland Government for a Flying Fox Roost Management Permit.

What you may do:

- Mulching and watering under or near roost trees

- Mowing and weeding

- Minor trimming of roost trees by hand. Up to 10 per cent of canopy in a 12 month period when flying foxes are not present

- Installation, maintenance or removal of infrastructure

What you can’t do:

- DO NOT TOUCH flying foxes. No touch, no risk.

- Low impact activities are not to disturb, drive away or otherwise negatively impact flying foxes

- Tree trimming must not be undertaken when flying foxes are within the tree or nearby (for example, within 10 metres)

- Roost trees are not to be removed.

FAQ: What is council's role in managing flying foxes?

Flying foxes are highly mobile wild animals. Their choices for roosting and feeding locations cannot be controlled or readily predicted.

Council's role is to monitor and advise people on how to minimise the impacts of living near flying foxes.

Ipswich City Council has voluntarily developed and adopted policies and plans related to flying fox roost management. Attempting to move a flying fox colony is called a dispersal. Flying fox roost dispersals are very expensive and rarely achieve the desired outcome.

Studies of historical flying fox dispersals indicate that colonies in general will move less than 500 metres from their original roost location if there is other suitable habitat. Given that most roosts are in urban areas, the problem is rarely solved and instead shifted from one location to another.

Council is committed to:

- Regular monitoring of known and new roosts

- Providing advice to community members

- Managing roosts on council land

- Enhancing habitat outside of urban areas.

Council will not undertake the following:

- Management of roosts on private land

- Dispersal or destruction of roosts.

FAQ: How can I minimise impacts from flying foxes?

For humans, flying foxes can create noise and smell. Flying foxes use sound as a means of communication, and as their hearing is similar to humans their calls are clearly audible to our ears.

Flying foxes use smell to help identify each other and communicate things like ‘keep your distance’. One dominant odour is a musk-like ‘perfume’ that males use to mark their breeding territories.

- Plan ahead for the summer influx by trimming trees near your house, swimming pool and other high use areas, removing understorey vegetation and mulching under trees (in accordance with the Code of Practice) before flying fox numbers increase

- Bring your washing in before dusk or install a clothesline cover

- Home upgrades such as double glazing and airconditioning enable windows to be closed in summer to reduce noise

- Park your car undercover

- Use fauna-friendly netting on your fruit trees

- Use a pool cover

- Avoid disturbances such as loud noises, as flying foxes make more noise when they are stressed.

For more information on the lifestyle of flying foxes and minimising their impact on daily life: Living Near Flying Foxes.

FAQ: What can I do to help flying foxes?

Flying foxes are critical for our environment, their pollination of plants is vital to many ecosystems, so it’s important we try to look after their populations as best we can. You can educate others on the importance of flying foxes and help to change people’s opinions of them.

Flying foxes are under threat due to a decline in feeding habitat and reduction in the number of suitable roost sites. You can increase the amount of feeding habitat available by planting native feed trees, such as eucalypt and paperbark trees away from houses on your property. Council's Free Plant Program provides a range of native species, subject to availability.

You can also volunteer to join a Bushcare group to help restore habitat along waterways which might one day become a suitable flying fox roost. Or you may like to support an Ipswich wildlife care group to help rescue and rehabilitate sick and injured wildlife.

Flying foxes are heavily impacted by droughts and bushfires which can significantly reduce the amount of pollen their feed trees are able to produce and the amount of water available for flying foxes to drink. During drought periods, keep an eye out for distressed or sick flying foxes and phone flying fox carers immediately. You can also supplement native wildlife’s water supply by providing clean water in a container secured in a tree.

Barbwire can destroy the bats’ mouths and wings. If possible, do not use barbwire. Another option is to cover the barbwire (with polypipe) or make it more easily seen (with reflective tags), next to flying-fox feeding or drinking places. If you have a barbwire fence which no longer serves a purpose, please, have it removed. Removing barbwire will also reduce injury to other wildlife such as birds and gliders.

Ideally netting should not be used at all, but if you must use netting to protect your fruit trees there are ways to reduce risk to wildlife. Loose netting and/or thin nylon/monofilament netting should never be used. See Netting Fruit Trees for more information.

Any bat found by alone during daylight hours is likely to be in trouble. It may be injured, sick, orphaned or electrocuted. In addition, bats in trouble seen between late September and January may be females and have young attached. Therefore, it is important to act as soon as you notice the animal.

- NEVER touch a flying fox. No touch, no risk.

- If a flying fox is injured or has come to ground in your backyard DO NOT TOUCH it, keep people and pets away and contact:

- Bat Rescue 3062 6730 (Ipswich)

- Bat Conservation and Rescue Queensland 0488 228 134

Further information

Ipswich City Council Flying Fox Roost Management Plan 2014 (PDF, 3.1 MB)

Ipswich City Council factsheet: Quick Guide to Living with Flying Foxes (PDF, 228.9 KB)

Bat Conservation and Rescue QLD website

Australiasian Bat Society website

Little Aussie Battlers website

BatPod 'choose your own adventure' podcast series for ages 10-15

Queensland Government Code of Practice: Low impact activities affecting flying-fox roosts, Nature Conservation Act 1992

Queensland Government information webpages

- Importance of flying foxes

- Living near flying foxes

- Flying fox viruses

- Mass dying events and heat stress events

- Flying fox FAQs

- Authorised flying fox roost management

- Bats and human health

New South Wales Government flying-foxes webpage

To notify of a suspected Hendra virus case contact Biosecurity Queensland on 13 25 23 (during business hours) or the Emergency Animal Disease Watch Hotline on 1800 675 888 (24-hour hotline).

Contact the Queensland Health hotline on 13 Health (432584) if you have concerns about possible exposure of people to Hendra virus or Australian bat lyssavirus.

Facts about flying foxes

Flying foxes have well-developed sensory systems and rely on eyesight, sound and smell to interact with their environment. They do not echolocate or use ultrasound.

Flying foxes spend hours grooming and practice exemplary personal hygiene. Their smell helps them identify each other.

Flying foxes weigh between 300 and 1000 grams, with an average wingspan of one metre.

They only take about 15 to 20 minutes to digest food and usually defecate a distance away from camps.

The wings of flying foxes have the same structure as human hands, with bones elongated to accommodate the wing membrane and support the body in flight.

Flying foxes drink by 'belly dipping'. They swoop down to a water source, dip their belly fur in, then land in a tree and lick the water from their fur.

Flying fox roosts are like airports, often containing different individual flying foxes each night.

Flying foxes have a strong allegiance to specific roosts, returning to them whenever they are in an area. These sites vary with individuals.

Roost locations are generally within 20-30km of flowering events, but roost locations are also influenced by temperature, rainfall, drought and bushfires.

One flying fox was tracked more than 12,733km. During that time, it travelled between 123 roosts and covered 37 local government areas.